Smile Train-Commissioned Study Reveals Deadly Reality of Malnutrition and Clefts

Globally, one in every 700 babies is born with a cleft, or nearly 195,000 each year. Currently, almost five million people live with an untreated cleft, leaving them susceptible to a number of potentially life-threatening conditions, including an increased risk of malnutrition.

Children with clefts younger than age five are far more likely to suffer nutrition-related issues than their peers. Globally, they are almost twice as likely to be underweight and at risk for growth failure.

Why? Clefts reduce babies’ ability to create suction during breastfeeding and bottle feeding, impact their ability to swallow, make food go into their lungs or out their nose, and make feeding more time- and energy-intensive than they handle without falling asleep. Collectively, these challenges result in lower intake of food and diminished health.

Smile Train, the world’s largest cleft charity, noticed a lack of global data related to clefts and malnutrition. So we partnered with the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) on a first-of-its-kind study to quantify the combined burden of malnutrition and clefts.

“We were interested in working with IHME to understand the burden of malnutrition in the global cleft population and the impact it has on malnutrition overall. Smile Train aims to raise awareness of these health challenges and to answer those questions that have never been answered on a global scale,” said Priya Desai, Smile Train’s Senior Vice President, Research, Data, and Evaluation.

To find our results, we merged the existing data in our proprietary database with estimates of the direct health consequences of malnutrition from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD), using underweight as a proxy to generate comparative estimates of the rate of malnutrition from 60 low- and middle-income countries in children younger than five years by age, sex, location, and year.

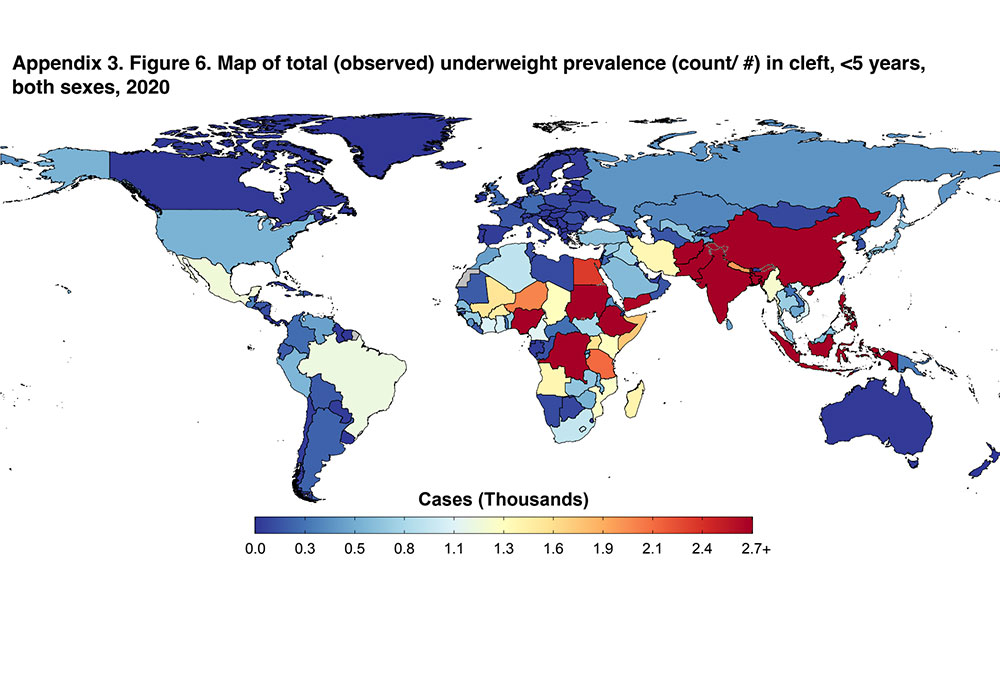

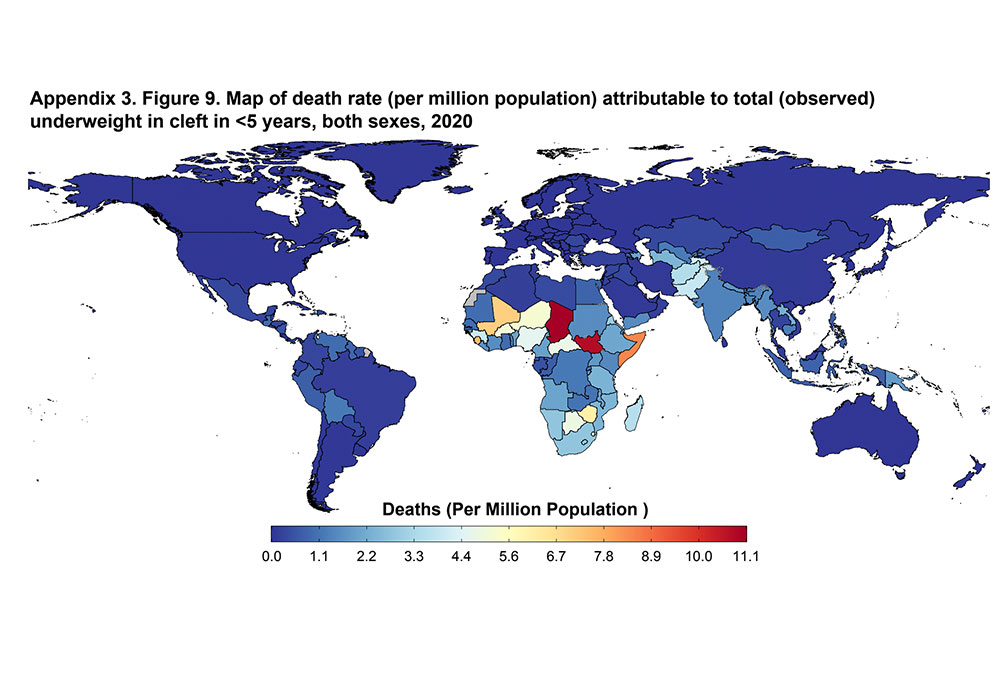

We found that, in 2020, nearly 600,000 children younger than five were living with a cleft. Of those, 200,000 were underweight. The highest cleft prevalence rates were in countries in North Africa and the Middle East, extending into Central Asia and South Asia. Cleft prevalence rates were lower in sub-Saharan Africa, with about 1 in 1,000 children having a cleft in those countries. However, sub-Saharan Africa (from the Sahel to the Horn of Africa) and South Asia had the highest rates of underweight conditions — increasing the vulnerability of those with clefts to malnutrition.

The data further indicates that children with clefts are more vulnerable to malnutrition, regardless of their economic, social, cultural, and political context. Between 2000 and 2020, more than 46,000 children with clefts died of causes related to malnutrition. Half of these deaths could have been prevented with access to adequate treatment and support.

Dr. Nick Kassebaum, a pediatric anesthesiologist and researcher in this collaboration, said that it is important to recognize “how much further [children with clefts] can fall behind and how much more vulnerable they are than the general population, needing extra attention to avert disaster.” Existing interventions and treatments include feeding modifications, specialized equipment and education for parents, psychosocial risk assessments, frequent weight monitoring, and surgery, preferably before three months of age.

While this is an extensive spectrum of interventions, the number of children born with clefts and the size of the under-five population with clefts suffering malnutrition have failed to decline significantly over the past 20 years. There remain 1.8 million children who are underweight solely because they have a cleft, and these cases are concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, warranting additional care in countries with both high cleft prevalence and underweight rates.

Dr. Kassebaum recommends that the interventions needed are twofold: “1) Support for nutrition itself in those who have never had cleft surgery, or who received it recently, and also the families of children with clefts. 2) Surgery. Clefts can be cured. So we need to make sure we can identify which children have clefts, give them care, and support the development of high-quality surgical services to take care of these kids and cure them.”

The study also finds that, to maximize the reach of prevention, identification, nutritional support, and surgical treatment services among children under five with clefts and their families, efforts must also take into consideration the disruptions to health services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread food shortages, and the remaining unmet needs of families.

Additional resources:

- GBD Compare - Child Growth Failure

- Think Global Health - Rethinking Ways to Address Child Growth Failure